simply amazing, always for you.

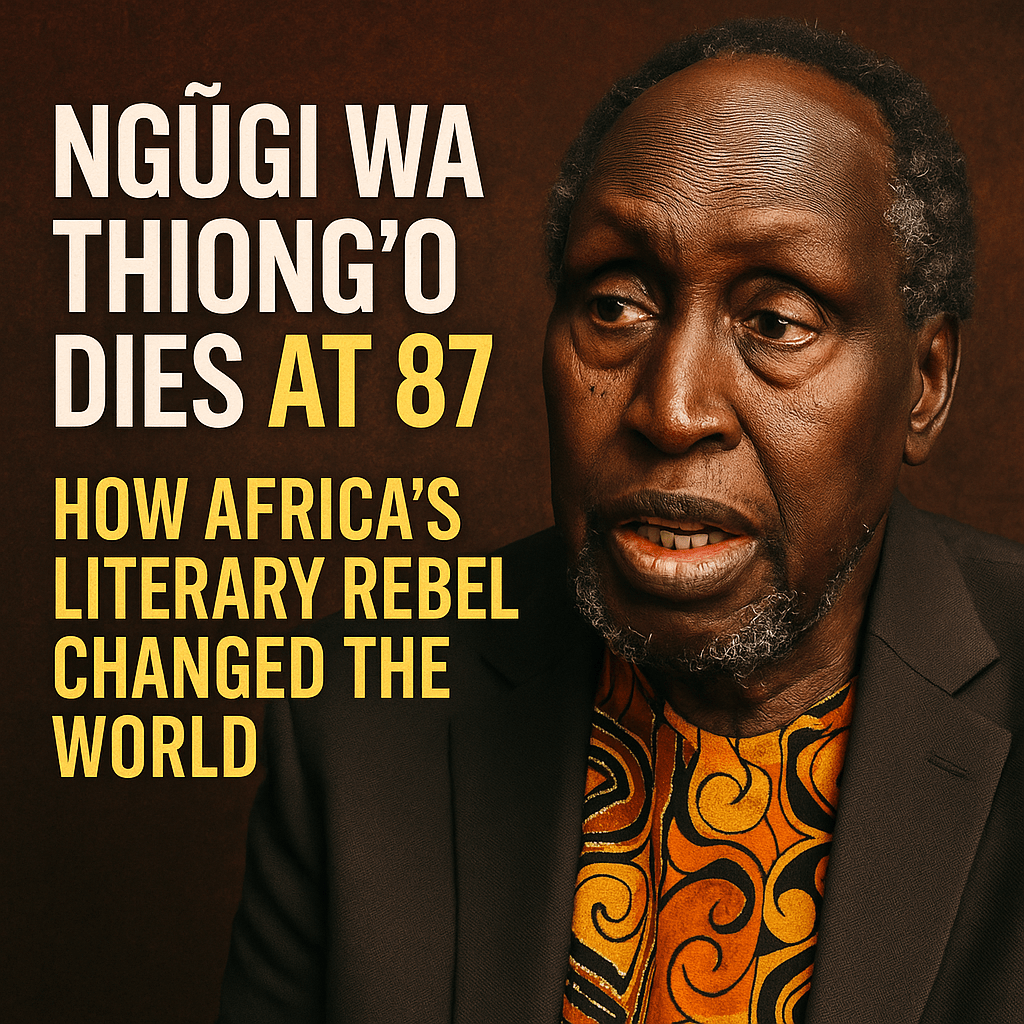

In the heart of a colonized Kenya, long before it was free, a boy named James Ngugi was born in 1938. Decades later, that boy would rise to become Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o—the man who redefined African literature, challenged imperial languages, and paid the price for telling uncomfortable truths.

On May 28, 2025, the world lost a literary titan. Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o died at the age of 87 in Buford, Georgia, USA, leaving behind not only a vast body of revolutionary literature but also a legacy of linguistic pride, resistance, and unrelenting commitment to truth.

But Ngũgĩ’s life was never just about books. It was about battles—against colonialism, cultural erasure, political oppression, and even language itself.

The Fire of Revolution in Every Word

To understand Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o is to understand a man who turned trauma into prose, and prose into power. Born in colonial Kenya, Ngũgĩ grew up in Limuru in a large, working-class family. His early years were marked by the upheaval of the Mau Mau uprising—a fierce, bloody struggle for independence.

As a student at Alliance High School, he witnessed the ravages of colonial punishment firsthand. When he returned home one school holiday, his entire village had been razed. His family was forced into British detention camps. One of the most painful chapters of his life came with the death of his brother, Gitogo, a deaf boy shot in the back for failing to respond to a British soldier’s command.

This brutal backdrop didn’t silence Ngũgĩ—it ignited him.

From English Laureate to Gikuyu Revolutionary

Ngũgĩ’s early novels, like Weep Not, Child (1964), The River Between (1965), and A Grain of Wheat (1967), made him a literary sensation. Written in English, they addressed the colonial experience and the human cost of resistance.

But something kept gnawing at him.

He began to question why he was using the language of the colonizer to tell the stories of the colonized. Why, he asked, should African writers express their truths in European tongues, while native languages like Gikuyu remained sidelined?

In 1977, Ngũgĩ made a bold turn. He co-authored a play, Ngaahika Ndeenda (I Will Marry When I Want), in Gikuyu. It was performed in a rural village and spoke directly to the plight of the common man. Its impact was seismic—and threatening to the authoritarian regime of President Jomo Kenyatta.

Ngũgĩ was arrested without trial and detained in Kamiti Maximum Security Prison.

Yet even there, he didn’t stop writing.

Using toilet paper and smuggled pens, he penned Devil on the Cross, the first modern novel written in Gikuyu. It was a defiant gesture—a symbolic breaking of chains.

Exile and Global Reverence

In 1982, following further harassment, Ngũgĩ went into exile. First in Britain, then the United States, where he eventually became a Distinguished Professor of Comparative Literature at the University of California, Irvine.

But exile never dulled his fire. He wrote, taught, and inspired new generations of writers to decolonize their minds—literally. His 1986 manifesto, Decolonising the Mind, became a foundational text in postcolonial studies. In it, he argued that language is not just a tool of communication, but a carrier of culture, history, and identity.

To Ngũgĩ, reclaiming African languages was not nostalgia—it was revolution.

A Lifetime of Unyielding Principle

Ngũgĩ’s commitment to justice came at a cost. He was banned in Kenya, blacklisted by publishers, and targeted by political enemies. In 2004, while visiting Nairobi after decades in exile, he and his wife Njeeri were attacked in what was widely viewed as a politically motivated assault.

Still, he returned, refusing to be exiled from his homeland in spirit.

His later work, including Wizard of the Crow (2006), showed a writer still at the peak of his creative power—blending satire, myth, and biting critique into an allegorical masterpiece.

Despite never winning the Nobel Prize for Literature, Ngũgĩ’s influence far outstripped many who did. He was awarded numerous honors, including the Nonino International Prize, the Erich Maria Remarque Peace Prize, and multiple honorary doctorates.

Yet, to many, the Nobel’s absence was a glaring omission.

A Farewell in Gikuyu and Grace

His passing was announced by his daughter, writer Wanjiku wa Ngũgĩ, who posted a heartfelt message on Facebook:

“It is with a heavy heart that we announce the passing of our dad, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o… As was his last wish, let’s celebrate his life and his work. Rîa ratha na rîa thŭa. Tŭrî aira!”

Translated loosely, the phrase means: “With joy and sorrow. We are proud.”

His son, author and academic Mũkoma wa Ngũgĩ, has also carried the torch of intellectual resistance, proving that Ngũgĩ’s influence is not just literary but generational.

Plans for public memorials and celebrations of his life are expected in the coming days. But one thing is clear: Ngũgĩ’s voice will never be silenced. His words live on—in books, in classrooms, in whispers of Gikuyu, and in the burning minds of those he awakened.

More Than a Writer—A Movement

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o was not just an author. He was a movement. A mirror for Africa to see its true self—not through foreign lenses, but through its own languages, cultures, and dreams.

He taught us that stories have power.

He reminded us that language is liberation.

He showed us that even prison walls cannot contain truth.

In his passing, we do not merely lose a writer. We lose a conscience, a rebel, and a visionary who dared to dream of an Africa that speaks in its own voice.

And now, that voice echoes louder than ever.

So what are we doing today—right now—to preserve, protect, and promote our native languages and stories, before they too are silenced?