simply amazing, always for you.

Original, In-Depth Feature

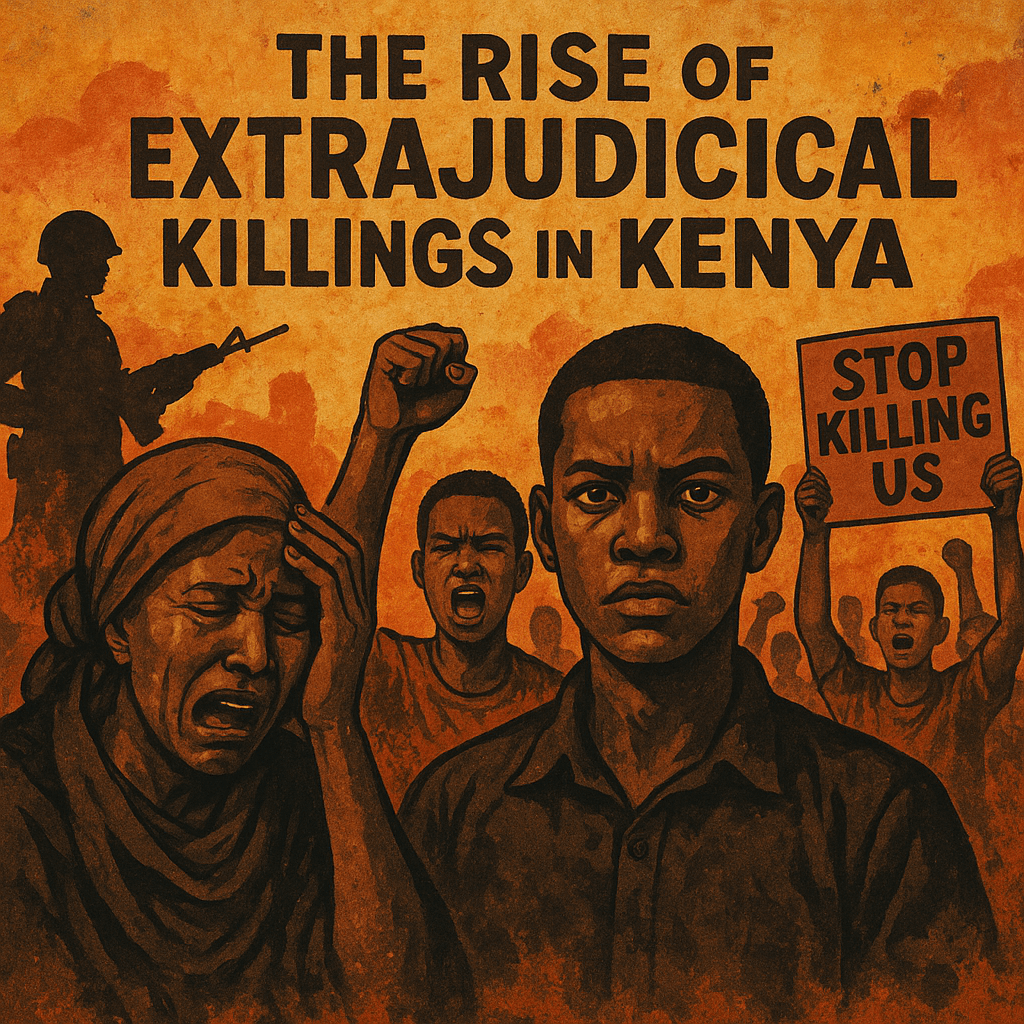

1. A Deadly Pattern Emerging

In the dusty, crowded alleys of Nairobi’s informal settlements, fear often walks before the police. When uniforms appear in Kayole, Mathare, Dandora, or Majengo, it is not uncommon for residents to shut their doors, send their children indoors, or disappear from the streets. The arrival of law enforcement rarely signals safety here. More often, it signals death.

Over the past decade, extrajudicial killings in Kenya—state-sanctioned executions without trial—have morphed from isolated tragedies to systemic atrocities. Human rights groups like Missing Voices Kenya and Amnesty International report hundreds of killings annually, mostly targeting young, poor, male Kenyans. Many are labelled as gang members or suspects, yet rarely is evidence produced, and even less frequently are the killers brought to justice.

This crisis has exposed a terrifying truth: in many Kenyan neighborhoods, justice is not blind—it is missing altogether.

2. The Faces Behind the Numbers

Beneath every statistic is a name, a family, a dream cut short. Take the case of Kevin Otieno, a 19-year-old bodaboda rider in Dandora. In January 2024, he was allegedly shot by a police officer during a routine patrol. The officer claimed Kevin was part of a gang. His mother, Janet Atieno, remembers things differently.

“He had just brought home some groceries. He said he was going to drop a friend near the junction and come back. He never returned.”

Kevin’s body was found hours later, riddled with bullets. No weapon was recovered. No witnesses dared testify. The case was closed before it ever opened.

Kevin’s story is echoed in dozens of others: Ahmed Hassan in Majengo, Peter Mwangi in Kayole, Samuel Kiprop in Eldoret. Many were last seen alive in police custody. Families mourn not just the loss, but the silence of justice.

3. Historical Context: A Legacy of State Violence

To understand how Kenya arrived at this crisis, one must look backward. The roots of police brutality run deep—back to the colonial era when the British created the police force to suppress dissent and enforce racial order.

After independence in 1963, the Kenyan state inherited this machinery of control and repurposed it. During Jomo Kenyatta’s reign, it was used to suppress political opposition. Under Daniel arap Moi, it became a blunt tool of dictatorship. Torture chambers like Nyayo House became synonymous with the state’s iron fist.

While the 2010 Constitution promised reform, including the creation of an independent police oversight body and a restructured police service, implementation has lagged. The old habits—targeting dissenters, silencing the poor, operating with impunity—persist.

4. Who Are the Victims?

The pattern is consistent. Victims of extrajudicial killings in Kenya are predominantly:

- Young men between 15 and 30

- From low-income or informal settlements

- With minimal access to legal representation

- Often accused of petty crimes or gang affiliation

In these neighborhoods, suspicion can be fatal. A boy with dreadlocks, a young man with tattoos, a late-night errand—any of these can be cause for lethal suspicion.

Women, too, are not spared. In 2022, a video of police officers assaulting a female vendor in downtown Nairobi went viral, triggering protests. The woman later died from her injuries. Justice, again, remains elusive.

5. State Justifications and the “War on Crime” Narrative

Officials often defend these killings under the guise of combating crime. In 2021, then-Interior CS Fred Matiang’i stated that the police were under pressure to “deal decisively with gangs.” Some officers have become media celebrities—dubbed “super cops”—for their shoot-to-kill tactics.

But this narrative is flawed and dangerous.

Crime, especially in low-income areas, often stems from poverty, unemployment, and systemic neglect—not inherent criminality. By treating poverty as a crime, the state criminalizes survival itself. The notion that “the end justifies the means” undermines the very rule of law.

6. The Role of Rogue Police Units

Some of the most egregious abuses have been tied to specialized police units, such as:

- Flying Squad

- Special Service Unit (SSU)

- Directorate of Criminal Investigations (DCI) tactical teams

Though some units like SSU have been disbanded after public outcry, insiders reveal that officers are often simply reshuffled—not held accountable.

In 2022, DCI officers were implicated in the disappearance and murder of two Indian nationals and their Kenyan driver. Their bodies were later discovered in Aberdare forest. After international pressure, the SSU was disbanded—but no senior officers faced prosecution.

These shadowy squads often operate without oversight, authorized to eliminate “threats” without warrants or trials.

7. IPOA, DCI, and the Justice System: Toothless Watchdogs?

Kenya’s Independent Policing Oversight Authority (IPOA) was created to monitor police conduct. But its bite has proven weaker than its bark.

- Out of thousands of reported killings, less than 5% have led to successful prosecution.

- Victims’ families are often too intimidated or impoverished to follow up.

- Witnesses fear retaliation and often go silent.

The Judiciary, slow and sometimes compromised, adds another layer of frustration. In some cases, courts have ruled against the police—yet enforcement is lax.

Meanwhile, internal police investigations are notoriously opaque. Officers implicated in abuse often remain on the force or receive quiet transfers.

8. The Weaponization of Poverty

Why are the poor so often the targets?

Because they lack the one resource that guarantees protection in Kenya: power.

Poor Kenyans often have no legal counsel, no social media influence, no media visibility. A killing in Kileleshwa makes headlines. A killing in Mathare becomes a statistic.

This disparity has led to a culture where the poor are dehumanized, viewed as disposable. Slum raids, forced evictions, street executions—these become normalized, expected.

And without public outcry, the cycle continues.

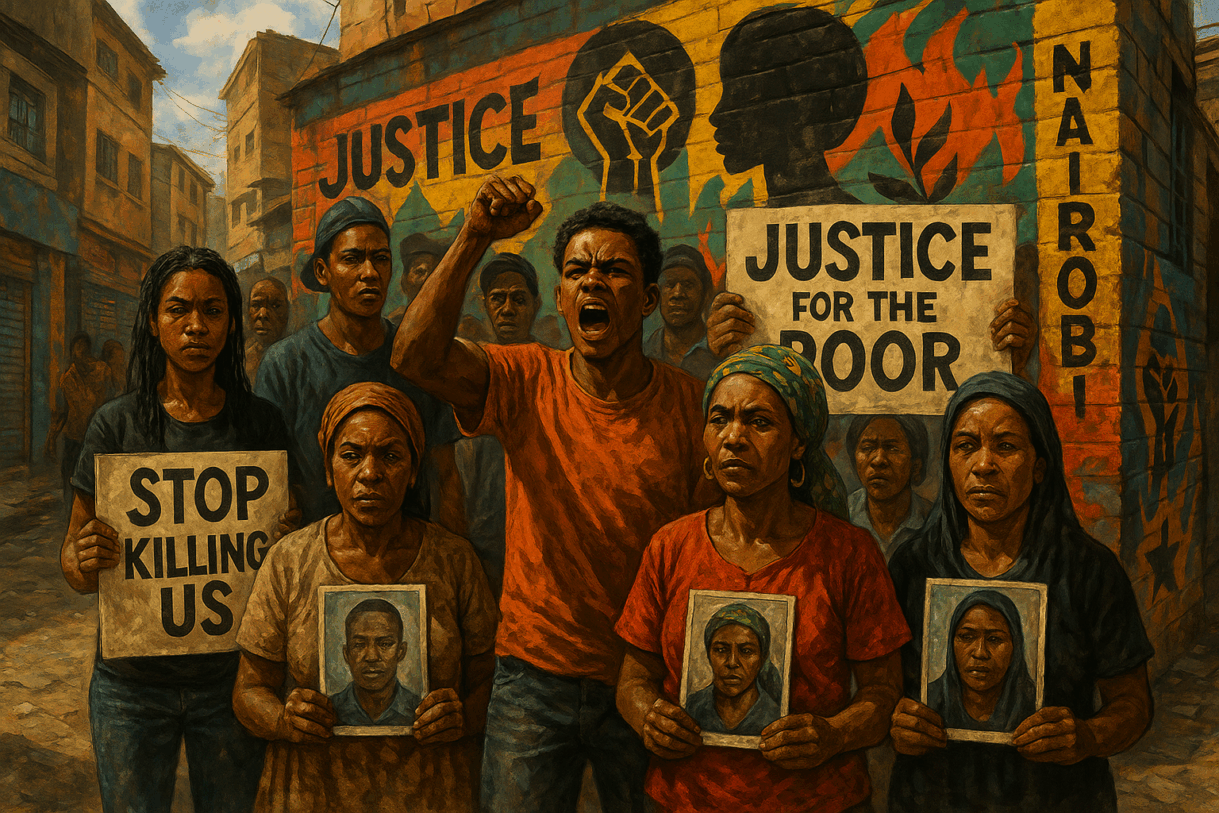

9. Voices of Resistance

Amid the despair, courageous voices are rising.

Boniface Mwangi, a prominent activist and photojournalist, has risked his life to expose police violence. His protest campaigns and street murals challenge the nation to confront uncomfortable truths.

Organizations like Missing Voices, Kituo Cha Sheria, and Muhuri are documenting abuses, filing cases, and empowering victims’ families.

Young people are also fighting back through art, poetry, music, and digital activism. Graffiti murals in Nairobi declare: “Stop Killing Us.” Slam poets turn pain into protest.

These efforts may not always stop the bullets—but they ensure the victims are not forgotten.

10. International Pressure and Human Rights Watchdogs

International organizations have repeatedly flagged Kenya for gross human rights violations. Reports by Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and UN Human Rights Council detail systemic abuses.

Ironically, many of the rogue units accused of killings have received funding, training, and equipment from foreign donors, including the UK, US, and EU under counterterrorism partnerships.

This creates a moral dilemma: foreign aid intended for security ends up financing abuse. In 2023, after the Indian nationals’ killing, India formally protested to Nairobi—leading to rare action. But without sustained pressure, these moments pass.

11. The Bigger Question: Who Protects the Poor?

This crisis reveals a deeper question about Kenyan society: who is justice designed to serve?

For the wealthy and powerful, there is law, process, and protection. For the poor, there is fear, bullets, and silence.

The state’s primary duty is to protect all its citizens. But when it turns its guns on the most vulnerable, it loses legitimacy. When police become executioners, and justice becomes a mirage, the social contract fractures.

Real security is not just the absence of crime—it is the presence of justice. It is the confidence that your life matters, even if you live in a shack or ride a boda boda.

Kenya at a Crossroads

Kenya is standing at a crossroads.

It can continue down the path of impunity, where the poor are hunted, the guilty are protected, and justice is an illusion. Or it can confront this darkness head-on.

Accountability must be more than a slogan. Police reform must be real, not cosmetic. IPOA must be empowered and insulated from political pressure. Rogue officers must be prosecuted—not transferred.

Most importantly, the Kenyan public must demand change. Because until the poorest Kenyan is safe from the gun, none of us truly are.

If a young man in Mathare cannot walk home without fearing death at the hands of those meant to protect him—what kind of nation are we building?

SUGGESTED READS

- How Youth Unemployment Fuels Radicalization in Kenya: The Silent Crisis

- Mungiki: The Rise, Fall, and Shadows of Kenya’s Most Feared Underground Movement

- The Rise, Evolution, and Impact of the Sungusungu Vigilantes in Kisii, Kenya

- The Mau Mau Rebellion: Kenya’s First War for Freedom

- Behind the Bars: The Most Dangerous Prisons in the World

Support Our Website!

We appreciate your visit and hope you find our content valuable. If you’d like to support us further, please consider contributing through the TILL NUMBER: 9549825. Your support helps us keep delivering great content!

If you’d like to support Nabado from outside Kenya, we invite you to send your contributions through trusted third-party services such as Remitly, SendWave, or WorldRemit. These platforms are reliable and convenient for international money transfers.

Please use the following details when sending your support:

Phone Number: +254701838999

Recipient Name: Peterson Getuma Okemwa

We sincerely appreciate your generosity and support. Thank you for being part of this journey!