simply amazing, always for you.

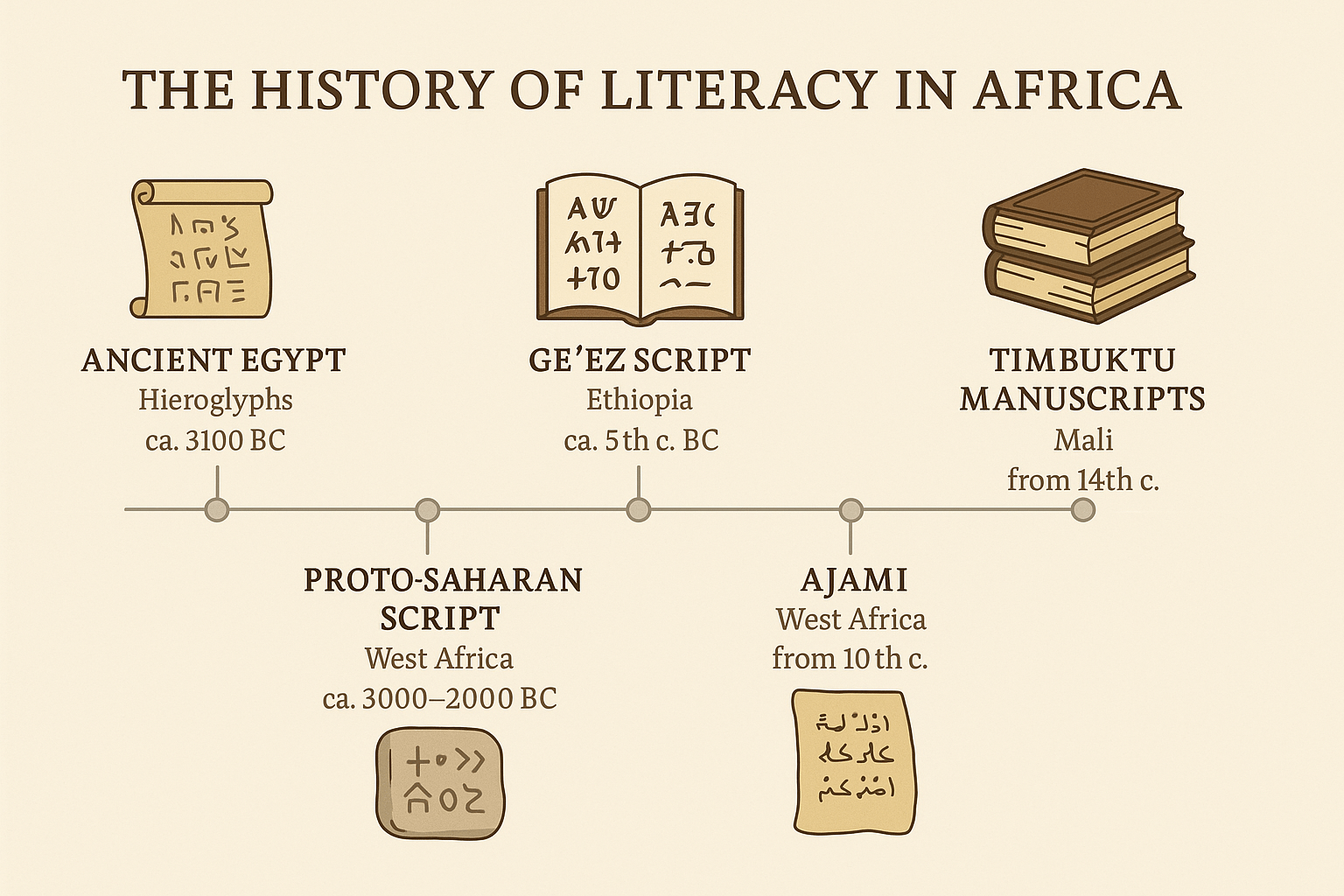

For centuries, the myth persisted that Africa was a continent without writing, without books, and without a tradition of scholarship. Colonial narratives painted a bleak picture: that literacy, learning, and intellectual sophistication only arrived with European missionaries and colonizers. But the evidence tells a very different story.

Long before colonialism, Africa had thriving literary traditions, complex scripts, and bustling centers of scholarship. From the hieroglyphs of ancient Egypt to the manuscripts of Timbuktu, Africans were not only readers and writers but also world‑class thinkers who contributed to global knowledge.

This article explores the fascinating journey of literacy in Africa, focusing on the legendary city of Timbuktu and expanding to other African traditions that prove the continent has always been a cradle of learning.

The Deep Roots of Literacy in Africa

The history of African literacy predates colonialism by millennia.

Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphics: The Dawn of Writing

One of the earliest and most iconic writing systems in the world, Egyptian hieroglyphics, dates back to around 3100 BCE. More than a script, it was a language of art and symbolism. Hieroglyphs appeared on temple walls, papyrus scrolls, and tombs, documenting religious beliefs, political events, and scientific knowledge.

The scribes of Egypt were revered figures. They mastered not only hieroglyphs, but also hieratic and demotic scripts used in administration and daily life. The Book of the Dead, a collection of spells to guide the soul in the afterlife, is among the best‑known examples of Egyptian literature.

Ethiopia and the Ge’ez Script

Moving east, the Horn of Africa became home to the Ge’ez script, one of the oldest alphasyllabaries still in use. Originating around the 5th century BCE, Ge’ez was the liturgical language of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church.

Texts written in Ge’ez included the Ethiopian Bible, one of the oldest complete Bibles in the world, and historical chronicles that recorded the reigns of Ethiopian kings. The script is still used today in Ethiopian and Eritrean churches, making it a living link to Africa’s ancient literary traditions.

Berber Tifinagh and the Tuareg Tradition

Across North Africa, the Berber people developed the Tifinagh script, still used today by the Tuareg communities in the Sahara. Tifinagh inscriptions appear on ancient rocks, monuments, and pottery, dating back at least 2,500 years.

For the Tuareg, Tifinagh was more than a script; it was a cultural identity marker. Women in particular played a significant role in preserving it, often teaching it informally within families.

Nsibidi: Africa’s Pictographic System

In West Africa, long before the introduction of Arabic or Latin alphabets, the Igbo and Ejagham peoples developed Nsibidi, a complex system of ideograms and pictographs. Believed to date back as far as 2000 BCE, Nsibidi was used for secret society communications, legal documents, and storytelling.

Because Nsibidi carried sacred and political meanings, it was not accessible to everyone, but its symbols remain a powerful reminder of indigenous African literacy.

Ajami: African Languages in Arabic Script

From the 10th century onward, literacy in many parts of West Africa spread through Ajami, the practice of writing African languages such as Hausa, Swahili, Wolof, and Fulfulde in Arabic script.

Ajami manuscripts included everything from poetry and songs to legal rulings and commercial records. They illustrate how Africans adapted an external script to preserve their own languages and ideas.

Timbuktu: The Jewel of African Scholarship

While Africa had many centers of literacy, none shone brighter than Timbuktu, the fabled city on the edge of the Sahara in present‑day Mali.

The Rise of Timbuktu

Timbuktu rose to prominence in the 13th century during the Mali Empire and later flourished under the Songhai Empire. Its strategic location along the trans‑Saharan trade routes made it a hub of wealth, attracting scholars, merchants, and travelers from across Africa and the Islamic world.

By the 15th and 16th centuries, Timbuktu had earned a reputation as one of the greatest intellectual capitals of the world, often compared to Cairo or Baghdad.

The Universities of Timbuktu

The city’s three great mosques — Sankore, Djinguereber, and Sidi Yahya — functioned as universities. Of these, Sankore University was the crown jewel. At its height, Sankore hosted up to 25,000 students, a remarkable number considering the city’s population hovered around 100,000.

Students studied:

- Islamic theology and law

- Mathematics and astronomy

- Medicine and pharmacology

- Literature, history, and philosophy

The curriculum was so advanced that students often traveled for months, even years, to join the scholarly community.

The Manuscripts of Timbuktu

Perhaps Timbuktu’s greatest treasure was its manuscripts. Historians estimate more than 700,000 manuscripts were written, copied, and preserved in the city and its surrounding regions.

These manuscripts covered:

- Science and Astronomy: Detailed charts of the stars, calendars, and explanations of eclipses.

- Medicine: Texts on surgery, herbal remedies, and treatments for diseases like malaria.

- Law and Governance: Trade agreements, property contracts, and legal rulings.

- History: Chronicles of African empires and royal lineages.

- Poetry and Philosophy: Works on morality, spirituality, and love.

They were written primarily in Arabic but also in Ajami, showcasing the diversity of African intellectual expression.

Ahmed Baba: The Scholar of Scholars

No story of Timbuktu is complete without Ahmed Baba (1556–1627), a prolific jurist and writer. He authored over 40 works and was widely respected across the Islamic world.

When Moroccan forces invaded Timbuktu in 1591, Ahmed Baba was captured and exiled to Marrakesh. Even in captivity, he continued teaching, proving that scholarship cannot be silenced. His works remain a cornerstone of African intellectual history.

The Fight to Preserve Timbuktu’s Legacy

Timbuktu’s manuscripts have survived against incredible odds.

- During the colonial era, many were looted or dismissed as irrelevant.

- Harsh desert conditions threatened their preservation.

- In 2012, extremist groups linked to Al‑Qaeda seized Timbuktu and declared the manuscripts heretical, burning some in public.

In an extraordinary act of courage, local librarians and families smuggled more than 350,000 manuscripts out of the city in rice sacks and metal trunks, often risking their lives. Thanks to their efforts, much of Timbuktu’s literary heritage was saved.

Today, digitization projects led by African and global institutions are making these manuscripts accessible worldwide while preserving the originals for future generations.

Women in Africa’s Literacy Story

The history of literacy in Africa is not only about men. Women also played vital roles.

One remarkable example is Nana Asma’u (1793–1864), a princess, poet, and scholar in Nigeria’s Sokoto Caliphate. She wrote extensively in multiple languages and organized a network of female teachers, spreading literacy among women and girls at a time when such opportunities were rare.

Her story reminds us that African literacy was not limited to elite men but was a shared pursuit across genders and communities.

Why This History Matters Today

The story of Timbuktu and African literacy matters for several reasons:

- It shatters colonial myths. Africa was not a continent without history or writing. It was home to world‑class intellectual traditions long before colonialism.

- It reclaims Africa’s intellectual legacy. The manuscripts of Timbuktu and the scripts of Ge’ez, Tifinagh, Nsibidi, and Ajami prove that Africans were knowledge producers, not just passive recipients.

- It inspires future generations. By studying these manuscripts, young Africans can reconnect with a heritage of scholarship that belongs to them.

- It enriches global knowledge. These works offer insights into science, law, and philosophy that complement and expand the human story of learning.

The first Africans to learn how to read and write were not students in missionary schools of the 19th century.

They were the ancient scribes of Egypt, the Ge’ez‑writing priests of Ethiopia, the Berber Tuareg with their Tifinagh inscriptions, the Nsibidi custodians in West Africa, and the scholars of Timbuktu.

Among them, Timbuktu stands as the crown jewel — a city of manuscripts, ideas, and scholars who believed that knowledge was sacred and worth protecting at all costs.

Today, as the manuscripts are digitized and shared, the world is finally beginning to recognize what Africans have always known: that their continent has been, and always will be, a home of wisdom.

SUGGESTED READS

- The Role of the International Criminal Court in African Conflicts

- Politics, Power, and Gangs: The Hidden Underbelly of Kenyan Elections

- Secret Societies and Oathing Rituals in Modern Africa

- Why Ibrahim Traoré Is Loved by His People: The Rise of a New African Icon

- The Rise of Extrajudicial Killings in Kenya: Who Protects the Poor?

Support Our Website!

We appreciate your visit and hope you find our content valuable. If you’d like to support us further, please consider contributing through the TILL NUMBER: 9549825. Your support helps us keep delivering great content!

If you’d like to support Nabado from outside Kenya, we invite you to send your contributions through trusted third-party services such as Remitly, western union, SendWave, or WorldRemit. These platforms are reliable and convenient for international money transfers.

Please use the following details when sending your support:

Phone Number: +254701838999

Recipient Name: Peterson Getuma Okemwa

We sincerely appreciate your generosity and support. Thank you for being part of this journey!

Greetings! I know this is kinda off topic but I was wondering if you knew where I could find a captcha plugin for my comment form? I’m using the same blog platform as yours and I’m having difficulty finding one? Thanks a lot!