simply amazing, always for you.

Whispers in the Alleyways

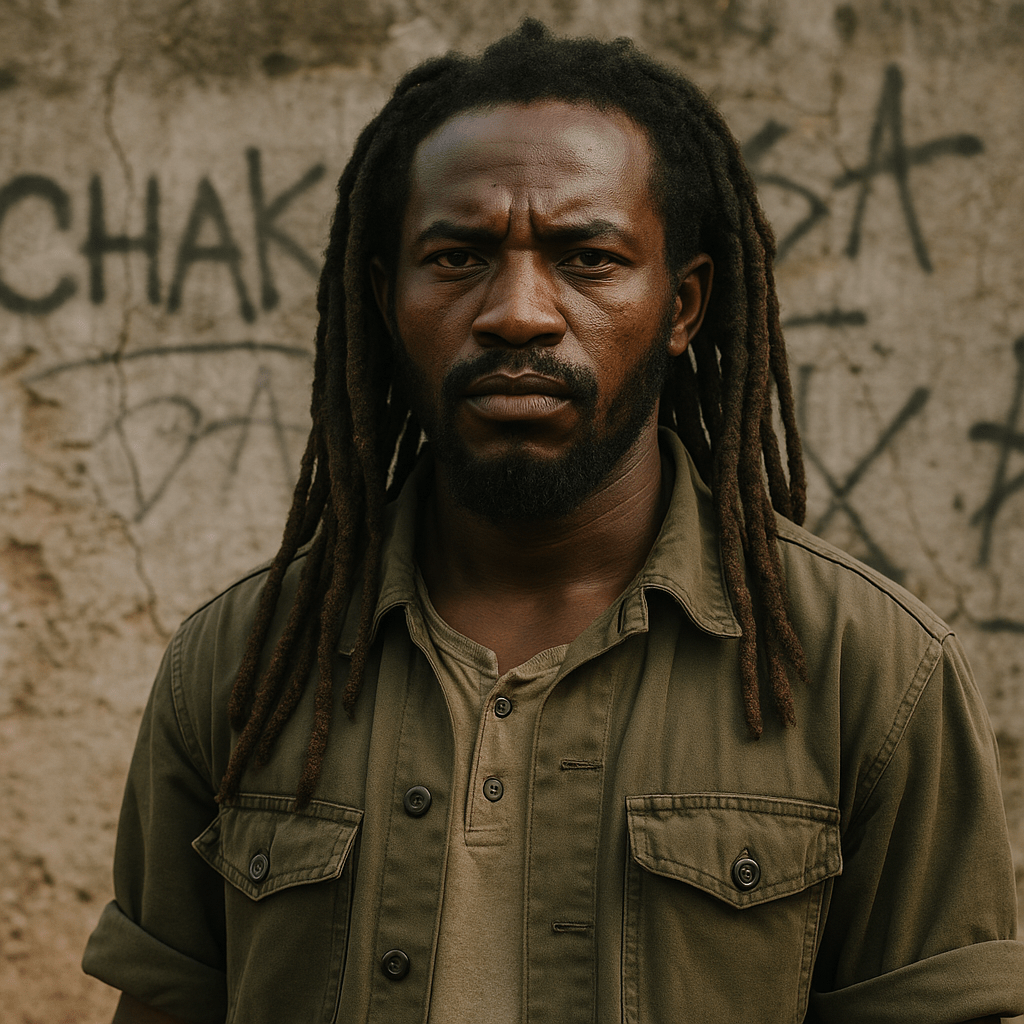

In the early 2000s, whispers of dread filled the slums of Nairobi. The name alone—Mungiki—was enough to silence a room. To many, it evoked images of machetes, oaths, dreadlocked young men, and violent revenge. For others, it was a misunderstood crusade—an indigenous revival that lost its way. But to understand Mungiki is not just to understand a movement; it is to stare into the soul of a fractured nation—one battling colonial hangovers, economic exclusion, and political betrayal.

This is the story of Mungiki, Kenya’s most enigmatic, controversial, and feared sect—a narrative of power, faith, violence, politics, and identity.

Chapter 1: Seeds of Rebellion — The Birth of Mungiki

Mungiki, meaning “a multitude” or “the masses” in Gikuyu, emerged in the late 1980s, born not in Nairobi’s ghettos but in the rural landscapes of Laikipia and Nyandarua. Initially, it was a spiritual movement—a Kikuyu youth-led revival of traditional customs and rejection of colonial legacies.

The founding members, mostly young disenfranchised men, claimed spiritual inspiration from the Mau Mau fighters who had resisted British colonialism in the 1950s. They wore dreadlocks in honor of the Mau Mau, rejected Western religion, and embraced traditional rituals and Kikuyu cultural values.

Their ideology was simple: restore purity, return to African roots, resist oppression. It was cultural at first, spiritual at best. But times changed. Kenya was transforming—and so did Mungiki.

Chapter 2: The Rise of the Urban Sect

By the mid-1990s, Mungiki had left the rural valleys and entered urban slums—particularly Mathare, Githurai, and Kayole. These overcrowded, chaotic zones were filled with unemployed youth, ethnic tension, and a vacuum of state control.

Mungiki filled the void.

They offered protection. They provided identity. They imposed discipline. They demanded loyalty.

Young men, frustrated by joblessness and poverty, found in Mungiki a place to belong. But belonging came at a price: oaths of allegiance, blood rituals, and unquestioning obedience. Disobedience meant death—swift and brutal.

Mungiki began controlling water points, toilets, electricity meters, and matatu (minibus) routes. They extorted daily fees from residents and drivers. Those who failed to pay were maimed—or killed.

Chapter 3: The Oath and the Blade

To be initiated into Mungiki was to cross a threshold—from a forgotten youth to a sworn soldier. New members took oaths involving goat blood, sometimes human blood, in secluded bush ceremonies. Once you swore in, you were no longer just a person—you were a vessel of the movement.

Oathing wasn’t merely symbolic. It was psychological warfare. It ensured loyalty, created fear, and bound the member spiritually.

Their spiritual base was rooted in Gikuyu traditional religion, led by “prophets” and “elders” who often operated in secrecy. Mungiki denounced Christianity as a colonial tool. Churches were not to be trusted. Instead, members worshipped Ngai—the Kikuyu God—from sacred spaces, often invoking ancestors.

They dressed in dark uniforms. Their leaders were rarely seen. Like the Mafia, hierarchy and discipline were strict. And like the Mau Mau, secrecy was sacred.

Chapter 4: Politics of the Blade — The Power Grab

As Kenya transitioned to multiparty politics in the 1990s, politicians noticed the growing clout of Mungiki. Here was a group that could deliver votes, intimidate rivals, and mobilize masses at short notice. Many politicians entered into secret pacts with Mungiki leaders.

Mungiki provided muscle. In return, they got protection.

The sect’s influence exploded. Matatu owners were forced to pay daily fees for “security.” Politicians paid them for rallies and riots. Some rumors even claimed that Mungiki helped “clean up” political opponents.

By the early 2000s, the sect was no longer just a cult—it was a parallel government in certain slums and rural towns. It enforced its own laws. Punishments included beatings, decapitations, and disappearances.

The state had created a monster—and now it had to deal with it.

Chapter 5: The Crackdown — State Strikes Back

The turning point came in 2002, after the fall of the Moi regime. President Mwai Kibaki’s government, under pressure to dismantle illegal sects, declared Mungiki a criminal organization.

Police raids began. Mass arrests followed. But what shocked the nation were the extrajudicial killings. Bodies of young men—many suspected Mungiki members—were found dumped on roadsides, hands tied, throats slit, or shot in the head.

Human rights groups estimated that over 500 Mungiki suspects were killed or disappeared between 2002 and 2008. Mothers wailed. Families buried empty coffins. Fear gripped the slums.

But Mungiki didn’t die—it went underground.

Chapter 6: 2007–08 — When Mungiki Came for Kenya

During the 2007–2008 post-election violence, Mungiki resurfaced—fiercer and more organized. Allegedly hired by politicians to defend “tribal interests,” they fought in Nairobi and Central Kenya.

Reports emerged of them collecting “security fees” from internally displaced people, threatening non-Kikuyus, and even retaliating against Luo and Kalenjin groups.

In retaliation, government forces intensified the crackdown. A secret police unit, the KweKwe Squad, reportedly executed dozens of suspects. One police spokesman even said: “We’ll kill them like rats.”

But as Mungiki bled, the political class remained eerily silent.

Why? Many still needed them.

Chapter 7: Death of a Leader — Maina Njenga and the Split

At the heart of the movement was one enigmatic figure: Maina Njenga. Charismatic, radical, and deeply spiritual, Njenga was the unofficial spiritual father of Mungiki.

He was arrested in 2002 and spent years in prison. Upon release in 2009, he claimed he had renounced Mungiki and become a born-again Christian.

But tragedy struck: his wife and bodyguards were assassinated in mysterious circumstances. Njenga blamed state security forces. The government denied involvement.

This marked the fragmentation of Mungiki. Some members followed Njenga’s spiritual turn. Others broke away, becoming more violent, forming rogue gangs, or aligning with political warlords.

The unified Mungiki was dead. But its shadow remained.

Chapter 8: Mungiki Today — A Ghost in the System

Officially, the government says Mungiki no longer exists. But in reality, the structure survives—broken, evolved, but not vanished.

Former Mungiki operatives have joined political campaigns, served as private security, or operate extortion rings under new names. Others formed groups like Jeshi la Mzee, Kamjesh, and Gaza Gang.

In rural areas, especially in Nyeri, Murang’a, and parts of Nairobi, whispers remain. People still fear naming names. Matatu drivers still pay “protection” money, just to newer faces.

And though today’s youth may not know the old rituals, the spirit of Mungiki—resentment, rage, and rebellion—still burns beneath the surface.

Chapter 9: Why Mungiki Rose — A Mirror on Kenya

To truly understand Mungiki, one must look past the machetes and media headlines. Mungiki was a symptom, not the disease.

It rose because millions of youth were unemployed. Because politicians used them like pawns. Because religion failed them. Because the state ignored their hunger.

It was a rebellion—not just of culture, but of dignity.

In a land where tribalism wins elections, where justice is for the rich, and where slums stretch endlessly—Mungiki made the forgotten feel powerful.

That is the scariest part.

Chapter 10: Lessons Kenya Can’t Ignore

Mungiki’s tale offers grave warnings:

- Youth without jobs become weapons.

- Cultural identity, when suppressed, festers.

- Politics and crime, when mixed, create monsters.

- Militias don’t die—they mutate.

If Kenya fails to reform—by creating jobs, healing tribal divisions, empowering youth, and fixing its justice system—the next Mungiki will rise. Perhaps not with dreadlocks, but with laptops and encrypted apps. And it may be worse.

The Ghost Still Walks

Today, Mungiki is a whisper. A rumor. A ghost.

But ghosts are born of the past we refuse to bury.

Behind every slum wall, behind every unemployed youth, behind every rigged election, the spirit of Mungiki waits—watching.

The machetes may be sheathed. But the rage? It simmers.

And until Kenya listens—not just with fear, but with understanding—the ghost will never rest.

SUGGESTED READS

- The Coffin Thief of Nairobi: The True Story of John Kibera

- The Dark Legacy of Okija Shrine: Nigeria’s Most Notorious Traditional

- How Foday Sankoh Led Sierra Leone into Chaos: The Ruthless Rise of a Rebel

- The Last Blessing: The Man Who Made It Rain From Heaven

- The Blood Oath: Rise of the Bakassi Boys

Support Our Website!

We appreciate your visit and hope you find our content valuable. If you’d like to support us further, please consider contributing through the TILL NUMBER: 9549825. Your support helps us keep delivering great content!

If you’d like to support Nabado from outside Kenya, we invite you to send your contributions through trusted third-party services such as Remitly, SendWave, or WorldRemit. These platforms are reliable and convenient for international money transfers.

Please use the following details when sending your support:

Phone Number: +254701838999

Recipient Name: Peterson Getuma Okemwa

We sincerely appreciate your generosity and support. Thank you for being part of this journey!