simply amazing, always for you.

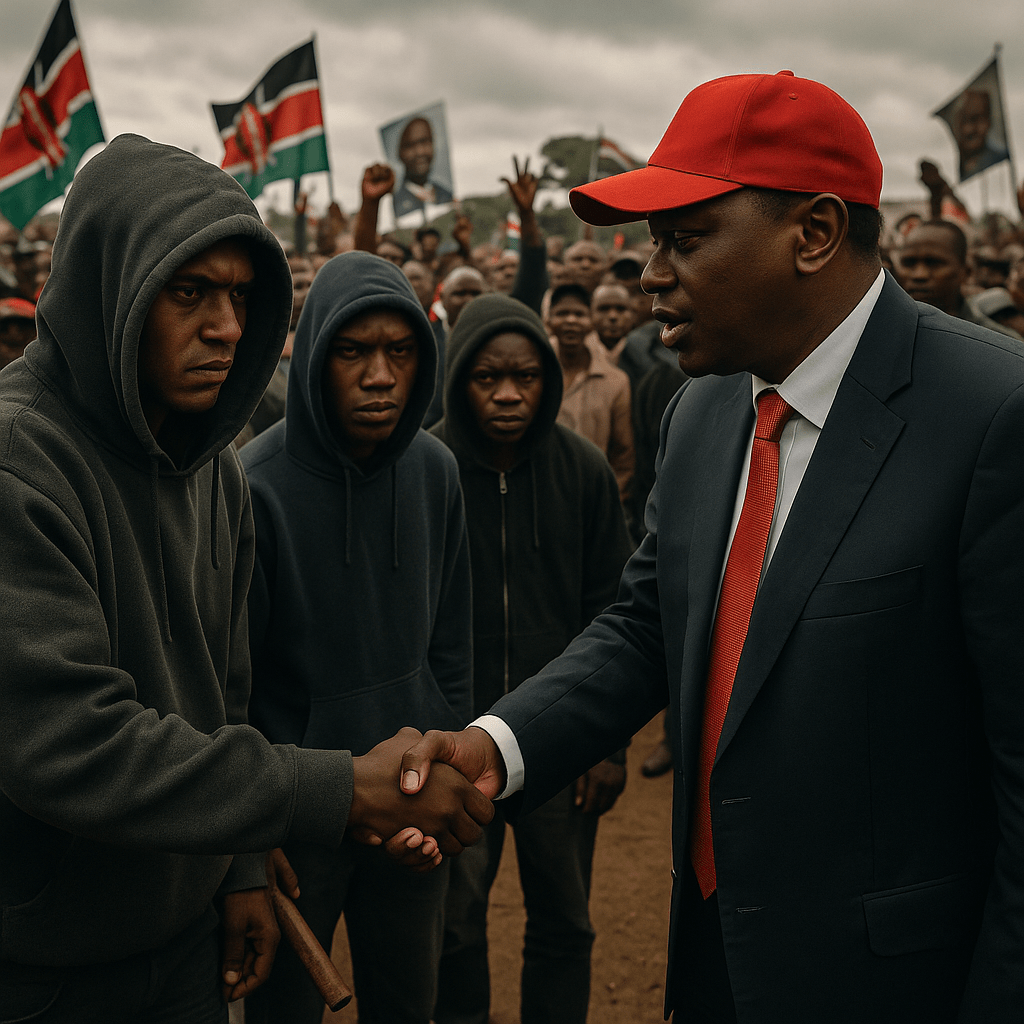

Politics, Power, and Gangs: The Hidden Underbelly of Kenyan Elections

Highlights the role of sects and gangs in political mobilization and violence.

Democracy’s Double Face

Elections are meant to be democratic rituals—moments when citizens assert their power to choose leaders and shape the future. In Kenya, however, elections often morph into battlegrounds where democracy is weaponized. Behind the polished campaigns and televised debates lurks a sinister machinery fueled by gangs, sects, and underworld operatives. Politicians don’t just campaign—they mobilize militias, contract street gangs, and activate ethnic sects. Votes aren’t just bought—they’re coerced, enforced, and in some cases, stolen through bloodshed.

This article takes a deep dive into Kenya’s dark electoral underworld. It unpacks how criminal groups—from Mungiki to Baghdad Boys—are courted, funded, and deployed in service of power. It explores the evolution of political violence, the commodification of youth in slums, and how oathing rituals, fear, and identity politics entrench this vicious cycle.

Chapter 1: A Legacy of Violence – The Roots of Political Thuggery

Kenya’s flirtation with political violence dates back to the early days of multiparty democracy in the 1990s. As opposition politics rose, so did ethnic polarization. The Moi regime was notorious for using militias and state-sanctioned repression to silence dissent. Groups such as the Jeshi la Mzee, loyal to KANU, were unleashed on rival communities.

What started as state-backed repression mutated in later years into freelance violence-for-hire. After Moi’s exit, political competition intensified, but the tools of power—violence, fear, and mobilization of identity—remained entrenched.

Chapter 2: Mungiki – The Prototype of Politicized Gangs

No gang encapsulates the toxic intersection of sectarianism, politics, and violence like the Mungiki. Born as a cultural-religious revivalist group in the 1980s, Mungiki evolved into a violent militia by the early 2000s, controlling informal settlements, matatu routes, and protection rackets.

By the time of the 2007 elections, Mungiki had become a political force—courted by top politicians for their capacity to mobilize thousands and enforce electoral dominance. In return, they demanded positions of influence, state protection, and lucrative contracts.

“Mungiki was the unofficial army of the political class. When politicians talked about votes, they were really talking about zones under control.” — Former police officer, Nairobi.

Their brutal oathing ceremonies, coded language, and underground networks made them both feared and indispensable. The 2007–2008 post-election violence saw Mungiki deployed as both attackers and enforcers, with chilling efficiency.

Chapter 3: The Informal Settlement Militias – Nairobi’s Powder Keg

Kenya’s urban poor—especially youth in slums like Mathare, Kibera, and Dandora—have long been pawns in political chess games. Here, gangs aren’t just criminal entities; they are political agents with loyalties, zones, and operational mandates.

Groups like:

- Baghdad Boys (Kisumu),

- Sungu Sungu (Kisii),

- Bungoma Boys, and

- Confirm Gang (Nakuru)

have become localized militias. Politicians fund them with cash, alcohol, and sometimes firearms in exchange for “security” and “mobilization.”

Mobilization, in this case, often means:

- Intimidating voters from rival camps

- Snatching ballot boxes

- Provoking or quelling riots

- Guarding campaign events

These gangs become kingmakers in tight contests, with entire polling stations under their grip.

Chapter 4: The Oathing Rituals and Ethnic Sects

In some regions, gangs are reinforced by ethnic sects and spiritual oaths. These rituals often bind youth to political loyalty in blood and fear.

- In Central Kenya, oaths administered by elders or rogue clergy may require recruits to swear allegiance to a political figure, or face spiritual death if they defect.

- In Kisii and Luo Nyanza, certain political candidates use cultural elders to confer legitimacy and impose psychological obedience through ancestral beliefs.

The line between cultural identity and political militancy is deliberately blurred—creating devotees rather than voters.

Chapter 5: The Role of Political Patrons and Dirty Money

Where does the funding for these violent networks come from?

- Campaign war chests (often looted public funds)

- Tenderpreneurs seeking contracts after elections

- Drug barons laundering through campaign contributions

- Corrupt government officials seeking protection after regime changes

Many gang leaders double as political mobilizers, brokering deals behind closed doors. In return, they are promised:

- Protection from police raids

- Lucrative contracts in construction and garbage collection

- Jobs in CDF and county offices

This transactional politics breeds a mafia-like ecosystem where violence, loyalty, and resource capture go hand-in-hand.

Chapter 6: Women, Youth, and Weaponized Poverty

Gangs often exploit economic desperation, especially among youth and single mothers. With unemployment above 35% among young people, many join gangs for survival.

Some are:

- Paid to attend rallies

- Used as digital warriors (trolling, spreading propaganda)

- Hired to “escort” politicians

- Used as voting mules, moving from one station to another

In some counties, women-led vigilante groups have also emerged, either resisting political violence or joining it for survival.

Chapter 7: State Complicity and Police Politics

Despite periodic crackdowns, Kenyan law enforcement is deeply entangled in political violence.

- Police chiefs receive orders from State House

- Local commanders are paid to look the other way

- Some officers are embedded in gangs as “intelligence” assets

Investigations into electoral violence are often half-hearted or weaponized. Suspects from rival camps are charged, while allied gangs walk free.

Even when commissions like Waki or Kriegler recommend prosecutions, the cases vanish quietly.

Chapter 8: Post-Election Season – Silence and Impunity

Once elections are over, gangs are either:

- Absorbed into local government projects

- Abandoned, leading to internal wars

- Eliminated through extrajudicial killings by the very state that used them

In 2013 and 2017, dozens of gang leaders and known mobilizers were executed in police operations. Human rights groups say these are cover-ups—a way to erase evidence and tie up loose ends.

“They use us like condoms—use and dump,” said a former Mungiki youth in Kayole.

Chapter 9: Can the Cycle Be Broken?

Kenya has tried various reforms:

- The Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC)

- Peace accords like “Handshake” (Uhuru-Raila)

- National Cohesion and Integration Commission (NCIC)

- Youth empowerment funds

But without political will, these remain cosmetic.

What’s needed is:

- Criminalization of political mobilization through gangs

- Prosecution of political financiers

- Witness protection programs

- Civic education and youth job creation

Above all, Kenya must de-ethnicize politics and create issue-based campaigns where violence isn’t a prerequisite for power.

Who Owns the Streets, Owns the Votes

Kenyan elections remain a brutal contest—not just of ideas, but of territory, identity, and fear. As long as gangs control the streets and sects control the minds, the ballot will remain hostage to violence. Politicians continue to walk the tightrope between democratic promises and militia proxies. And in the middle, the voter—hungry, scared, and hopeful—is left to survive another election cycle.

Can Kenya ever hold truly peaceful elections without first dismantling the power of gangs and sects in politics?

SUGGESTED READS

- Maina Njenga: Prophet, Cult Leader or Political Pawn?

- Secret Societies and Oathing Rituals in Modern Africa

- Matatu Mafia: Inside Kenya’s Deadly Public Transport Cartels

- Why Ibrahim Traoré Is Loved by His People: The Rise of a New African Icon

- The Rise of Extrajudicial Killings in Kenya: Who Protects the Poor?

- Top 10 Most Notorious Gangs and Militia Groups in Africa

- How Youth Unemployment Fuels Radicalization in Kenya: The Silent Crisis

Support Our Website!

We appreciate your visit and hope you find our content valuable. If you’d like to support us further, please consider contributing through the TILL NUMBER: 9549825. Your support helps us keep delivering great content!

If you’d like to support Nabado from outside Kenya, we invite you to send your contributions through trusted third-party services such as Remitly, western union, SendWave, or WorldRemit. These platforms are reliable and convenient for international money transfers.

Please use the following details when sending your support:

Phone Number: +254701838999

Recipient Name: Peterson Getuma Okemwa

We sincerely appreciate your generosity and support. Thank you for being part of this journey!